On the eve of mental health awareness month, a clip of John MacArthur made its way around the website formerly known as Twitter. In it, the pastor of Grace Community Church in Southern California denied the existence of such mental disorders as PTSD, OCD, or ADHD. He claimed that these diagnoses were simply “noble lies” that Big Pharma used to give psychologists license to medicate people, stating that mental illness was, in reality, the result of an inability to cope with life and to take responsibility for one’s actions. This is but one recent instance in a longer history of evangelical denial of mental illness.

For those familiar with MacArthur, the ideas expressed in this clip were neither new nor surprising. But as someone whose research examines the history of evangelical attitudes toward mental health and modern psychology, I find MacArthur’s comments remarkably reminiscent of an earlier strand of opposition to modern psychology that has flourished in some evangelical circles since the 1960s. It is these older arguments that MacArthur recycles, even as broad swaths of the evangelical world see no contradiction between a life of faith and the science of the mind.

For centuries before the advent of modern psychology, many Christians considered care for the “soul,” long thought to encompass the mind and emotions, to be among the most vital responsibilities of the church. As the psychologist replaced the pastor’s authority on the mind in American society, conservative white Protestants in the twentieth century developed an ambiguous relationship with the new science. By midcentury, many evangelicals sought to reverse the perceived cultural separatism of their fundamentalist forebearers, engaging readily with academic disciplines like psychology. Evangelical psychologists simultaneously worked to demonstrate that psychotherapy and theology could indeed coexist—that, as they often put it, all truth was God’s truth (even when that truth was ascertained through academic research). These evangelicals founded professional organizations like the Christian Association for Psychological Study (1956), academic journals, and accredited doctoral programs at such institutions as Fuller Theological Seminary (1965) and Biola University (1968) to train evangelical psychologists to meet the mental health needs of the church. These efforts were, by and large, successful in bringing the insights of modern psychology into the evangelical mainstream.

But while these efforts helped to equip Christian psychologists and pastors to offer aid to those suffering, their efforts prompted backlash among other evangelicals. The most well-known example was that of Jay Adams, Presbyterian pastor and father of what became known from the late 1960s onward as the “biblical counseling movement.” Under Adams, this movement was initially premised on several assumptions.

First, that human beings consisted of body and soul, exclusively; what psychologists and others conceived of as the “mind” fell under the broader category of soul. This resulted in a dualistic anthropology that collapsed mind, soul, and spirit into a single, immaterial category. Whereas Christian psychologists wrestled with the complex relationship between body, mind, and spirit, believing that these facets of the human being were inextricably, if mysteriously, connected, Adams believed that human beings consisted only of body and soul and, furthermore, that these two categories existed in isolation from one another.

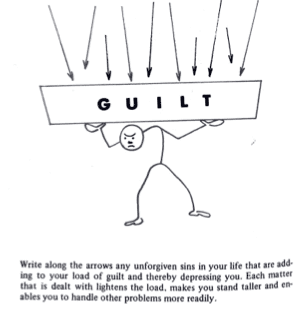

That “mental illness” occurred not within the mind but within the soul meant, in Adams’ estimation, that psychological issues were, at root, spiritual issues. This line of thinking transformed mental illness into moral illness. Even before founding the biblical counseling movement, Adams had become convinced that psychotherapy merely functioned to absolve the guilty by casting wrongdoing as mental or emotional illness. In recalling his early attempts at pastoral counseling before adopting a “biblical counseling” approach, Adams’ wrote: “I found myself asking, ‘Is much of what is called mental illness, illness at all?’” (Adams, Competent to Counsel, xi). This pastor became increasingly convinced that most instances of mental illness stemmed from hidden sin. Addressing readers in 1970, he offered the example of persistent drunkenness, claiming that what the Bible labeled as a “sin” most mental health literature called a “disease.” Adams went on to theorize that other psychological diagnoses, such as depression, more often than not were the result of compounded guilt for unrepentant sins. (Given that Adams saw it as the pastor’s role to confront the sins of those who came to him, he often referred to his approach as nouthetic counseling, from the Greek word meaning “to admonish.”) He illustrated for readers the effects of this guilt with the graphic below:

Adams set forth these views in, Competent to Counsel (Zondervan, 1970), the book which has perhaps become his most influential publication. Competent to Counsel advanced a twofold thesis: 1) that knowledge of Christian Scripture made ministers (and even Christian laypeople) entirely competent to counsel the faithful through any kind of intra- or interpersonal disturbance, and 2) that most problems that therapists labeled “psychological,” were, in fact, the result of sin. This stance stemmed, in part, from Adams’ counseling experiences in his early years as a minister; he recalled frequent feelings of incompetence when faced with counseling church members, who he perceived to be in need of professional psychological help. Increasingly, Adams grew frustrated with his lack of an alternative to secular psychological offerings. Concerning counseling, he interpreted the growing prominence of psychologists in American society as a threat to the authority of both the pastor and the Bible. Adams’ answer to this conundrum resulted in the publication of Competent to Counsel, which ignited the biblical counseling movement.

Another undergirding principle of Adams’ biblical counseling included his belief that Scripture must be the foundation of any knowledge system; any other epistemic foundation was fundamentally flawed. Adams interpreted and employed the arguments of theologian, Cornelius Van Til, as justification for his stance, writing that, “at bottom, all non-Christian systems demand autonomy for man, thereby seeking to dethrone God” (Adams, Competent to Counsel, xxi, fn. 1). For Adams, this epistemological position further undergirded his argument that pastors alone bore the credentials to offer guidance to suffering Christians. “Rather than defer and refer to psychiatrists steeped in their humanistic dogma,” he wrote, “ministers of the gospel and other Christian workers who have been called by God to help his people out of their distress, will be encouraged to reassume their privilege and responsibilities” (Adams, Competent to Counsel, 16).

This brought Adams into conflict with Christians who made a vocation out of the integration of theology and psychology, even as he demonstrated a failure (or unwillingness) to meaningfully engage with the viewpoints of those he criticized. He expressed staunch opposition to opponents, not only in print but in person, too. After giving a guest lecture at Biola’s Rosemead Graduate School of Psychology in the 1970s, Adams declared to students and faculty, “This program has no reason for existence, not only can you not integrate pagan thought and biblical teaching, but what you are trying to do is to train people to attempt the work of the church without ordination, outside the church. That is distorting God’s order of things” (Adams, More Than Redemption, 276). The address was, predictably, poorly received among his audience of professional counselors, who considered themselves part of the church, and, therefore, carrying out the work of the church, within the setting of a counseling clinic. What these faculty and students saw as a ministry of healing, Adams attacked as the employment of pagan principles that served only to dethrone God.

What began with Adams’ fast-selling book on biblical counseling turned into a full-fledged movement by the close of the 1970s. However, large swaths of the biblical counseling movement have undertaken a marked departure from Adams’s ideas and tone in recent decades. The largest biblical counseling organizations have softened their rhetoric, eschewing Jay Adams’ combativeness for a message decidedly less confrontational. It is now common to find biblical counselors, who affirm the connectedness of body, mind, and soul, as well as the reality of mental illnesses. More biblical counselsors quietly have become open to the use of some scientific research and psychotropic medications, while foregrounding care for the suffering, rather than rejecting psychology in their writings and practices. Still, Adams’ shadow looms large in many corners of this movement.

In many ways, MacArthur’s stance and rhetoric bear remarkable similarities to those of his pastoral counseling predecessor. Similar to Adams, MacArthur has long espoused the belief that the human soul encompasses the mind, and that counsel for the human soul is exclusively the purview of the pastor. But what’s more, he has carried on Adams’ penchant for oversimplification—and outright misrepresentation—of theories, individuals, and entire disciplines, since the 1980s. As far back as 1989, MacArthur warned in sermons that “insidious” psychology had infiltrated the church and country. Messages like this, for the last several decades, not only have failed to offer an accurate depiction of psychological treatment, but also have played consistently upon base human fears.

The aforementioned clip and an ensuing follow-up essay are no exception to this pattern. In the clip, MacArthur constructs a treacherously slippery slope from medication to drug-addicted homelessness, redirecting the anxieties of his listeners from public issues to psychiatry. Reading MacArthur’s follow-up piece, one might get the idea that all psychiatrists (and psychologists as well) readily prescribe addictive medication to the detriment of the individual and society, as they claim that these medications bear a 100% chance of alleviating every symptom of which a patient complains.

Like Adams, MacArthur also has refused to listen and meaningfully engage with brothers and sisters in the church, whose work, research, and experiences run counter to his claims. Indeed, for decades Christian mental health professionals have demonstrated that a life of faith (and often an evangelical faith, at that) need in no way be incompatible with modern psychology. And, unlike the 1960s, one can’t chalk up a dearth of engagement with these voices to an ignorance of their existence or to the inaccessibility of their work. There are now countless examples of faithful Christians, writing about the integration of Christianity and psychology for laity, academic audiences, and everyone in between; one cannot in good faith claim that this information is unavailable or that these voices are, in the words of MacArthur, “attacking biblical sanctification.”

Yet, this dearth of engagement, with qualified interlocutors, fails to take seriously the experiences of fellow believers, who testify to the help and healing mental health treatment has provided, which in no way is at odds with a vibrant life of faith. Tragically, this posture has had serious repercussions, beyond burning bridges with fellow Christians committed to alleviate the mental suffering of many.

In the worst of cases, this has manifested in tragic cases of abuse, including at MacArthur’s own Grace Community Church. Serious allegations have been made concerning instances of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, which were not reported to authorities. Furthermore, those affected were not referred to mental health professionals. Rather, these instances were treated as the result of a departure from Scriptural teaching. In insulating congregants from the supposed danger of professional mental health services, the church also insulated sufferers of abuse from safety, justice, and legal recourse.

So, to be clear, what is troubling here is not the conviction that insights from Christian scripture or Christian belief could help ease mental and emotional suffering. As a Christian myself, I’ve anecdotally found this to be the case, but scientific research also testifies, in its own way, to the psychological benefits of religious belief, practice, and community, much of which finds its foundation in Scripture. No, what’s troubling about the recent discourse is the refusal to listen or meaningfully engage with brothers and sisters in the Church—whose work, research, and experiences run counter to MacArthur’s claims—and the insistence in doubling down on such stances, even when the fruit of those stances has proven to be so harmful to many. What’s troubling is that these statements obscure, for many listeners, the heart of a God who sees the suffering, hears their cries, and draws near to the brokenhearted.

Skylar Ray (Ph.D., Baylor University) is Assistant Professor of History at John Brown University. She is a specialist in religious and cultural history of twentieth-century United States. Her dissertation—“Healing Minds, Saving Souls: Evangelicals and Mental Health in the Age of the Therapeutic”—examined the evangelical relationship to modern psychology and its therapeutic function in treating issues of mental health.