The debate between creationism and evolution is a continuously popular one in Christian circles. Much of the conversation is relegated to philosophy and abstract apologetics. But also interesting is the history of how evangelicals have reckoned with this conversation throughout time.

We begin with the history of the well-known Scopes trial, a hallmark moment for creationists in America. Then, we visit the lesser-known Moody Institute of Science (MIS). This was an institute that chose to engage with the culture through producing scientific films. These films highlighted the compatibility between Christian faith and modern science.

These MIS films are helpful for thinking about how Christians reach out to others using the language and knowledge of the day. And they are helpful for remind us about the internal divisions within Christianity that are always at the backdrop in our Christian lives.

For we cannot think about how to engage with the world without also thinking about the internal diversities within Christianity over how to engage with the world. We may have an idea of how to advocate for justice, feed the poor, heal suffering, or preach the Gospel. But at all times, our idea will not be the only one within the broader Church. Ignoring this may work for a time, but in the long term we must be able to reckon with doctrinal and ideological diversity within the Body of Christ.

The Scopes Trial

I. The Beginnings

The Scopes trial, also known as the Scopes Monkey Trial, is an incredibly important event in American history. The story begins with the Butler Act in 1925. This act forbade the teaching of evolution in Tennessee public schools and universities.

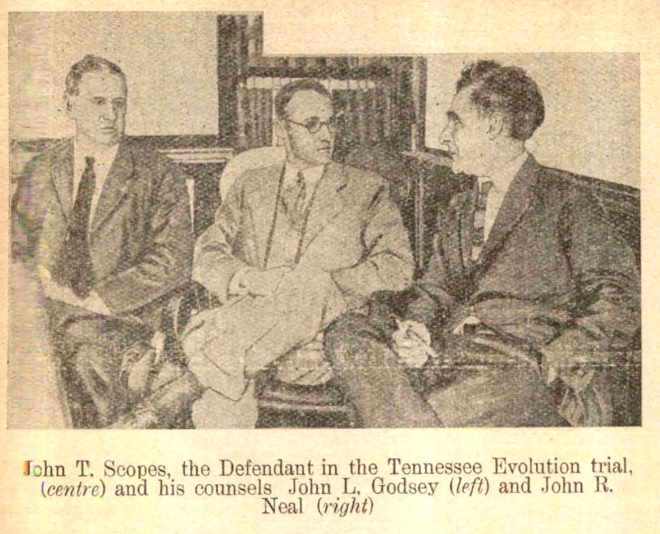

The Scopes trial was a direct response to this act. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which is still involved in religious liberty cases today, decided to put the act under legal scrutiny. The ACLU posted an ad in the paper. The ad called for anyone willing to challenge the act in court. John Thomas Scopes, a highschool teacher in Dayton, Tennessee, was urged by community leaders to take up the challenge.

The plan was that Scopes would violate the Butler Act by teaching evolution in his class. Once the school took disciplinary action, Scopes and the ACLU would sue in an attempt to overturn the Butler Act.

II. The Scopes Case Begins… and Ends

And so, after Scopes got caught teaching evolution in his classroom, the case began. The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes quickly increased in publicity. Representing John Scopes was Clarence Darrow. In the attorney world at the time, Darrow was at the top in criminal law. The state’s attorney was William Jennings Bryan, a former Democratic politician who also staunchly believed in biblical literalism. Both men were incredibly high-profile.

With such heavy-hitting attorneys, media flooded into the small town of Dayton. The legal theatrics could very well equated with Judge Judy’s TV show, if the Scopes trial did not exceed it.

But as the case went on, the trial ended in favor of the state. Scope was fined and lost the case. The Butler Act remained on the books until 1967.

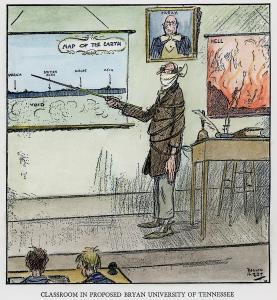

But though the anti-evolutionists had won the case, in very important ways, they lost the culture.

The Creationists Retreat

The fact that the Butler Act could have been passed in 1925 is not significant. What is significant was the amount of support that got the Act passed. In Tennessee’s House of Representatives, the Act passed on a vote of 71 to 6, and the state Senate passed it 24 to 6! This support, especially in the House, was overwhelming.

The explicit language of the Act is revealing; it was explicitly religious. The Act held “[t]hat it should be unlawful . . . to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”

Christian creationists had had a good amount of political influence. But after the Scopes trial, things took a turn. As Heather Hendershot writes in Shaking the World for Jesus: Media and Conservative Evangelical Culture, “The Scopes trial received wide newspaper coverage, and conservative Christians (and Southerners) were portrayed as stupid, irrational, and backward.”

The negative press led fundamentalists to retreat from the world. There is much more to write on what exactly they were doing between the Scopes trial and the 70s, when they reemerged in the public consciousness. But suffice it to say, the Scopes trial represented a major cultural loss for conservative Christians.

Science Films for Jesus

From 1945 to 1962, the Moody Institute of Science (MIS), affiliated with the Moody Bible Institute, produced and showed thirty films in public spaces like schools, fairs, and churches. These films highlighted the compatibility of Christianity with science.

The films were not, like the Butler Act, considered overtly religious until the 60s. And yet, they showed wider audiences how religion was neither superstitious nor anti-science. Just twenty years after the Scopes trial, when religion and science were pitted against each other, this was a significant message.

As Heather Hendershot points out in Shaking the World for Jesus, these films coincided with the so-called neo-evangelicals who “were spearheading a movement away from fundamentalist separatism [and] toward evangelical worldly involvement.” Unlike the fundamentalists, these new evangelicals wished to engage with the world rather than retreat from it.

These films won plenty of “worldly” approval. Some of the experimental demonstrations wowed not just general audiences, but professionals. The 1957 film Red River of Life received publicity in Scientific Monthly. The Journal of the Society for Motion Picture and Television Engineers covered multiple MIS films. Irwin S. Moon, the filmmaker behind MIS’s projects, was a weekly guest on the Steve Allen Show for a time.

Internal Tensions after Scopes

But the success of the MIS was not representative of the entire evangelical/fundamentalist world at the time. It would have received criticism for watering down the Gospel and gaining the approval of sinners.

Most certainly, fundamentalists of the time would have seen MIS’s silence on the question of evolution to be a compromise for worldly attention and approval. MIS was cognizant of this difficulty. Dr. Will H. Houghton, the fourth president of the Moody Bible Institute, made some interesting remarks on the fundamentalists.

Deeply involved in the creation of the MIS, Houghton knew the fundamentalists quite well. He wrote that some fundamentalists “have little knowledge but deep prejudices in the realm of science . . . It is not our job to start a new reformation and move fundamentalism out of its inclination to think with its emotions.”

In other words, Houghton observed that the strongest opposers of evolution were those that knew least about it. This meant that their critiques were grounded in insecurities in their faith, rather than scientific and logical argumentation.

Lessons from MIS on Creationism and Science

The MIS films are interesting because they represent the perennial tension between being in and not of the world. The fundamentalists who retreated from the culture after Scopes simply refused to be in the world. And MIS, working in a secular film industry and showing its productions in public spaces, risked becoming of the world.

Yet, its films successfully sparked conversations on the relationship between faith and science. It engaged the culture on the terms of the culture. And, most importantly, members like Dr. Houghton knew the internal tensions within and across Christian communities that existed on questions of evolution. And he addressed those tensions in an informed and steadfast way.

Each generation of the Church is faced with one or more important moments or tests. Our answers to these tests will be the fruit by which we are known to be faithful or unfaithful (cf. Matt. 17:15-20). So, each generation must step out in faith to address the issues of the day.

For each answer given by some Christians, there will be criticism from others. There might never be a solution that all Christians agree on. So as we try to live out our lives as faithfully political Christians, we must be cognizant of our fellow Christians who disagree with us. We must learn their positions and reasons, and try to build solidarity and community across those political differences.

Out of that dialogue, our own approaches should be solidified and edified, further grounded in the truth, even if we must change our minds. We cannot be like those fundamentalists who, as Houghton put it, opposed most what they knew least of.