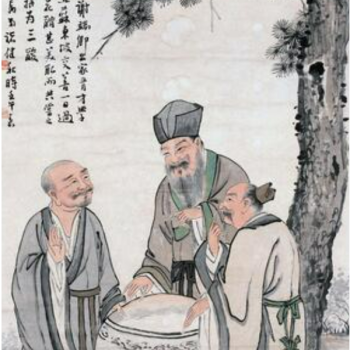

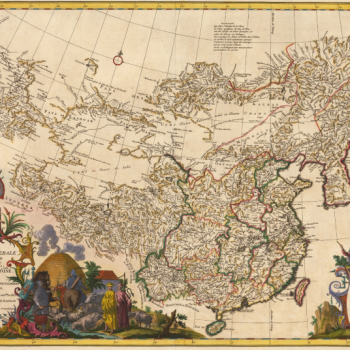

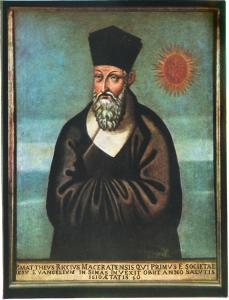

The return of the Catholic Church to China began with the Jesuits. In the last decades of the sixteenth century, these enterprising missionaries began preparations for a big push into the country, setting up a mission in Portuguese-ruled Macau in 1563. They would make the jump across the water in 1583, under the leadership of Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci. Landing in the far south, in the town of Zhaoqing in Guangdong, the Jesuits established their first mission on the mainland. Only five years later, in 1588, Ruggieri would be recalled from Asia. But Ricci would stay on as leader of the Jesuits in China until his death in 1610. He would spend the next eighteen years on a slow but steady march northward, culminating in the founding of a mission in Beijing itself in 1601. Thus began a remarkable period of missionary activity that lasted from the very last decades of the Ming into the first few centuries of the Qing Dynasty.

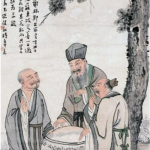

Popular depictions of Catholic missionaries often portray them as brutally stamping out native culture and thought in their efforts to introduce a hegemonic interpretation of Christianity—and there is often an uncomfortable amount of truth to such depictions—but in China, at least initially, the situation was different. The Jesuits under Ruggieri and Ricci’s leadership proved to be surprisingly accommodating of Chinese culture. When they set up their first mission in Zhaoqing, they did so in the guise of Buddhist monks. They soon abandoned that particular ploy but, in the years afterward, refashioned themselves as distinguished Confucian scholars. Ruggieri and Ricci both recognized how deeply rooted the whole of Chinese society was in Confucianism. So instead of displacing it, they tried to coopt it for their own purposes, much as the Church had once done with Greek philosophy. The Jesuits argued that Confucianism was a pre-Christian system of ethics and metaphysics that did not inherently contradict Christ’s teachings, and thus it could be allowed to continue alongside them. Ruggieri and Ricci seem to have somewhat grasped the old truth I have often highlighted here, that in the Chinese religious landscape, new ideas do not displace old ones so much as learn to coexist with them.

And so the Jesuits, particularly Ricci, accommodated themselves to this truth, at least as far as Confucianism is concerned. They offered no such olive branches to Buddhism or Taoism, assumedly because both religions made stronger demands on their followers regarding such things as gods and the afterlife. But with Confucianism the Jesuits were willing to strike an accord. Thus, these Christian missionaries took up Confucian dress, wrote catechisms in Mandarin and treatises on the wisdom of Confucius, and gave consent for Chinese Christians to continue traditions such as ancestor worship that would normally be considered blasphemous by the Church. It was this policy of accommodation that allowed the Jesuits to gain a foothold in the mainland as well as—in the early years at least—avoid persecution from the imperial authorities, who were apparently lulled by Ricci’s assimilationist efforts into thinking of Catholicism as simply an eccentric new kind of Confucianism.

In the end, however, this policy earned them few friends on either side. The imperial courts of the Ming and Qing often tolerated the Jesuits, sometimes relied upon their expertise, and occasionally favored them with high office, but never fully trusted them. Imperial authorities seemed to be waiting for any slip up on the Jesuits’ part in order to move against them. Indeed, the ever-paranoid Qing Dynasty launched a full-scale persecution campaign in 1664 and, while this was relaxed after a few years, the Jesuits and Catholic missionaries were left painfully aware that their foothold in the country hung by a thread, capable of being snapped at any moment by the whims of a capricious emperor or those he gave his ear.

In 1632, the Franciscans and the Dominicans took advantage of Jesuit successes to plant their own missions in China. If the Jesuits hoped that the arrival of their co-religionists would make things easier, they were very mistaken. One suspects that Joachim, with his surprising open-mindedness to other faiths such as Judaism and insistence on following “the spirit, and not the letter” of Catholic teaching, might have agreed at least in part with how the Jesuits set about establishing themselves in China. But the two orders of which he was the intellectual godfather did not. They pursued a more hardline approach to proselytism that refused to make any concessions whatsoever to Confucian practice and the established traditions of China. These two, along with the other mendicant orders that gradually made their way into the country, routinely criticized the Jesuits and complained to Rome incessantly about their supposed watering-down and compromising of the faith. This sparked the Chinese Rites Controversy.

That controversy proved catastrophic for not only the Jesuits but also Catholicism in China more generally. In 1704, the Pope finally intervened in the controversy, ruling that Jesuits had to abandon their conciliatory policies toward Confucianism. Henceforth, Chinese converts to Christianity would have to let go of their Confucian practices and cultural traditions. This did not sit well with the Qing Dynasty, which responded by demanding that Catholic missionaries obtain an imperial license to preach. The Kangxi Emperor would only grant these licenses if the applicants accepted Confucian practices and did not prevent their Chinese followers from carrying them out. The missionaries, constrained by the Pope’s decree, refused. The Kangxi Emperor responded in 1707 by tearing up his own Edict of Toleration—which had granted the missionaries a protected status—and launching another persecution of Catholics.

It was a disastrous double blow. Catholic missionaries in China would now have to contend with periodic Qing persecution. But their newly mandated opposition to all things Confucian also alienated them from the populace. The Chinese people would not give up traditions so deeply engrained in their culture and this foreign faith’s insistence that it possessed the only truth made no sense to a public so used to casual syncretism in their religious affairs. The difference and rivalry between the Jesuits and the mendicants had already kept Christianity from growing much in China. But the harsh and exclusivist attitude now universally adopted by the missionaries rendered Christianity—whether Catholic or Protestant—unappealing to the vast majority of the population until much later in history.

In these difficult centuries of Catholic missionary effort, there was one group amongst the wider populace to whom the new European arrivals’ teachings did appeal, and that was China’s Three Ages sects. Due to the successful push by teachers like Gongchang to foster unity among these sects, their members now viewed themselves as parts of a larger sectarian movement. And they were quick to recognize the newly arrived Catholic Church as one of their own. This process started almost immediately. Yu Liu, in “The True Pioneer of the Jesuit China Mission: Michele Ruggieri,” records a curious incident that occurred only a few years after the founding of the first Jesuit mission on the mainland:

In 1587, a Chinese convert named Martin came from Macao or Guangzhou to Zhaoqing and used his familiarity with Ruggieri to defraud two other new local converts, a father and a son. Knowing the father and son’s prior interest in alchemy, he tricked them into receiving large sums of money by pretending that he could pass on the secret of turning mercury into silver from the European missionaries who were then widely reputed for being knowledgeable in the art. (Yu 381)

This incident was a source of great difficulty for the Jesuits. the hostile reaction it produced from local authorities posed the first real threat to their presence in mainland China. It probably played a role in Ruggieri being recalled from the mission the next year and Ricci being installed as overseer in his place. However, Ricci would face the same sort of trouble himself, as Yu relates: “In spite of a friendship of more than ten years with him, for instance, Qu Taisu (1549–1612), whom Ricci regarded as one of his most cherished converts, was known to have rekindled a Daoist interest in alchemy only two or three years after entering the church and to have even attempted to persuade Ricci into the devious practice,” (382). It seemed that no matter who was in charge of the Jesuit missionary effort, they could not avoid becoming entangled with heterodox Chinese beliefs and practices. And as it turned out, this would only be a foreshadowing of things to come.

These two incidents are more relevant to our purposes than it may seem. The practice of alchemy had long been practiced in China, particularly by Taoists. But the Three-Ages sectarian movement had also from its very beginnings maintained a key interest in the subject. Alchemical practices formed a core part of their teachings and, indeed, they were the main purveyors of alchemic thought and theory by the time the Jesuits arrived in China. Within the baojuans themselves, alchemy seems to have largely been spiritualized, becoming a matter of regulating internal bodily energy carried out through meditative techniques rather than of reconfiguring real metals through physical experiments. But some initiates still took this alchemical language literally and looked for ways of actually carrying out alchemical processes in the material world. Thus, when we encounter practitioners of alchemy among the general populace in sources of this time, it is likely that we have once again come face to face with members of Three Ages sects.

Thus, these two events tell us two important things. One is that a number of converts to Catholicism came from the Three Ages sects. Another is that they apparently saw the teachings of the Jesuits as similar to the ones preached in those sects. Yu acknowledges in the Ruggieri anecdote that the missionaries were “widely reputed for being knowledgeable” in alchemy. This suggests that the Chinese saw them as being the same type of religious teacher as the Three-Ages sect leaders, who also taught alchemy and were famed for their aptitude in it. Qu Taisu’s attempt to interest Matteo Ricci in alchemy provides further support for this conclusion. Qu was Ricci’s close friend and star convert. If anybody should have understood the content of Ricci’s teachings, it was him. And yet, he thought that Ricci’s teachings had room in them for alchemical speculation. This suggests that, even after over a decade of close association, he still viewed Ricci’s Catholicism has fundamentally the same as the doctrines of his original Three Ages sect. If someone with as much access to Ricci as Qu had felt this way, it must certainly have been a common assumption among Chinese who had less access to the personal lives of the new arrivals. It seems that, from the beginning, Catholicism was simply regarded as another form of the Three Ages sectarian tradition that had long since rooted itself in the Chinese religious landscape.

A curious sequence of events taking place over a hundred years later provides even more direct proof that Three Ages sectarians viewed Catholicism as merely another sect within their own faith tradition. The location of these occurrences will surprise no one who has been following this series thus far. It was Shandong, birthplace of Patriarch Luo and Puming and eternal hotbed of sectarian sentiment. R. G. Tiedemann records the particulars in the article, “Christianity and Chinese ‘Heterodox Sects’: Mass Conversion and Syncretism in Shandong Province in the Early Eighteenth Century.”

In the early years of the eighteenth century, Shandong was the epicenter of Christian efforts in China. Both the Jesuits and the Franciscans had set out to convert the province and maintained a strong presence. The Dominicans had also arrived; their activities in the region had helped to spark the first great wave of Qing persecutions in the 1660s. What is more, the Bishop of Beijing and head of the Church in China, Della Chiesa, had moved his residence out of the national capital and to Shandong in order to avoid the hostility of the Qing court. As a result, Shandong became the most Christian of Chinese provinces. Tiedemann observes, “Here the missionary work flourished particularly during the last years of the Kangxi reign, at a time when the spread of Christianity was already experiencing a degree of retardation in other parts of China” (347). But here, it was not among the urbane classes or the big cities that the missionaries found their success. Rather, “evangelistic work showed most promise amongst the peasantry in the countryside” (347). This was, as we know, the social class most likely to be involved in the Three Ages sects. We would expect, then, that at least some of these new converts to have once been members of those sects.

Such expectations, however, would be far too modest. As it turns out, an overwhelming majority of converts to Christianity were Three Ages sect members. We saw above how, from the earliest days of the Jesuit mission, Catholic Christianity seemed to hold a special appeal for Three Ages sectarians. The Catholic Church noticed this as well. Unable to make much headway amongst the other classes and social groups in China, they began to prioritize bringing members of the Three Ages sects to Christ. Tiedemann notes, “At the time both Catholic and Protestant missionaries were well aware of the considerable conversion potential amongst what were commonly referred to by missionaries at the time as ‘secret sects’ (mimijiao 秘密教)” (344). In this endeavor, the missionaries found great success; they brought many Three Ages sectarians into the Church throughout northern China and, Tiedemann adds, “similar mass conversions to Christianity had taken place amongst such secret folk sects in western Shandong during the first quarter of the eighteenth century” (344). Thus, the Three Ages sectarians became the only social group in China to convert to Catholicism in any appreciable numbers during these centuries. This might have all been to the Church’s benefit if not for the fact that few of the new converts saw the need to cut ties with their old faith just because they had entered a new one.

Within a religion as convinced of its own special claim to truth as Catholicism and in a political scene as fraught with danger as that of the Qing Dynasty, this peculiar situation could only lead to turmoil. With no real understanding of the inherent syncretism that underly all Chinese popular religion and the beliefs of the Three Ages sects in particular, the Catholic Church assumed that these new converts were exclusively loyal to their new religion. But the converts saw no reason why they could not accept the faith of Christ and still believe in the teachings of their old sects. After all, had not the most celebrated of sect leaders, like Patriarch Luo, Yin Ji’nan, Piaogao, and Puming, joined several different faiths before founding their own? Had most of those sect leaders not taken the teachings of those previous sects with them when they eventually founded their own? Had not Gongchang and his successors preached the unity of all sects—indeed, all Chinese religions—as individual embodiments of the same universal truth? They had, of course, done all these things. By the eighteenth century, it was common for individual sect members to imitate their venerable forerunners, joining many different sects over time but accepting all of their teachings as expressions of the same doctrine. They saw no reason for this newest sect, the Catholic Church, any differently.

The Church, accustomed to—and much responsible for—the more exclusivist mindset toward religious affiliation prevalent in the West, failed to grasp any of this. Their naivete and the excitement generated by their apparent successes made them reckless. In Shandong, much of their later troubles stemmed from one man, a Franciscan missionary by the name of Francesco Nieto. Nieto was tireless in his efforts and seemingly quite effective. In the five-year period between 1709 and 1714 he had managed to convert 10,000 people to Christianity—a tiny fraction of the populace, yes, but far more than what any of his fellow missionaries were able to achieve. But he also seems to have been rather sloppy in his preaching. He never made it clear to his new disciples that their previous allegiances were incompatible with the faith they had just joined. As a result, many sectarians passed into the Church without understanding that they had to forsake their old beliefs or sectarian loyalties.

The missionary Miguel Fernández Oliver would later claim that “Nieto was not instructing his people well and hence had not been able to get rid of the ‘sect’” (356). Inevitably, there were going to be consequences for this mistake. But Nieto himself does not deserve all the blame. His superiors seem to have been so satisfied with the remarkable advance of the gospel in China that they did not question his results until subsequent events forced them to. In this manner, the Catholic Church itself precipitated the constant state of crisis it would find itself in during the early eighteenth century when it became clear just how deeply the Three Ages sectarians had infiltrated their community in Shandong.

By 1713, the Church was already becoming accustomed to occasional disturbances from the sectarians. In 1703 and again in 1712, they discovered that local sectarians, upon learning the rituals and practices of the Catholic Church, set up their own sects using the name Tianzhujiao (天主教—Teaching of the Lord of Heaven)—the Chinese name for Catholicism—that imitated Church rituals such as penance and confession. For the sectarians, this was par for the course. Aspiring sect leaders would frequently use the name and rituals from one of their previous sects when founding a new one—we saw this with figures like Piaogao and Gongchang. But the Catholics, possessing a worldview in which the unity of the One Church was paramount, viewed this as sacrilege and blasphemy of the highest order. Unfortunately, they also saw it merely as an example of the fundamental dishonesty of the unconverted and failed to recognize it for what it was, a sign of how thoroughly their own flock was involved in sectarian activities.

Thus, the Church walked blindly into a more tumultuous series of events that began in 1713. In this year, the Dong’e county magistrate received word that Three Ages sectarians had begun entering the Catholic Church. He launched an investigation which apprehended and punished four recent converts, much to the Church’s chagrin. The next year, in 1714, it came to light that a Three Ages sect had come into being within the ranks of the Church itself. Tiedemann quotes the words of a Jesuit missionary named Girolamo Franchi on this movement: “‘a band of villains’ … had started an uprising and formed a new sect, ‘but in order to disguise it did not hesitate to request Holy Baptism which they did receive upon adequate instruction’” (351). Franchi would try to pass this situation off as a matter of deceit, with the sectarians receiving baptism and instruction in the Catholic faith only as a cover for their own activities. By his account, the sectarians were never sincere in their pledges to the Church and thus the Church’s entanglement with them was brief, trivial, and accidental.

But he gives the lie to his own claims when he states, “One who is now known as an arch-sectarian previously was so chaste, zealous and pious that nobody suspected the wolf in such false sheep’s clothing, so the Father appointed him a church elder to be a leader of the other neophytes” (qtd. in Tiedemann 352). This was no mere passing acquaintance on the part of the sectarians, then. One of their own number had been in the Church long enough, formed a close enough relationship with the missionaries, and excelled enough in Catholic teaching to be made a church elder. This man was, according to Tiedemann, an individual with the surname of Zhang and the Christian name of Paulus (Paul). According to Della Chiesa, the Bishop of Beijing, “Zhang had been baptized about four years previously by Nieto in Dongping zhou, and had become a sincere Christian” (353), subsequently earning the trust of Carlo Orazi da Castorano, a prominent missionary. Orazi appointed Zhang to the office of zonghuizhang (總會長—church elder), which meant that Zhang, despite being a layman, would be in charge of several congregations in Shandong—a necessary measure given how few priests were in China at the time. What is more, the bishop also notes that “Zhang was engaged in evangelistic work not only for Orazi, but also for Franchi in the border area of Dong’e, Changqing and Chiping xian, where their respective Christians were intermingled” (353). Clearly, in his four years in the Church, Zhang Paulus must have shown himself to be an exemplary Christian because not only did he rise to high office in the Church, but he also gained the friendship and trust of the most respected missionary leaders in the area at the time.

It is true that not everything was rosy. Tiedemann observes, “In due course, Zhang seems to have fallen out with Franchi and become involved in a dispute with the latter’s Christians. Furthermore, Franchi accused Zhang of being a ringleader of a rebellious sect, with some 10,000 members” (353), which may explain some of Franchi’s hostility in his account—although the need to protect his reputation and that of the Church is probably explanation enough. Regardless, it is clear that Zhang’s understanding of Catholic doctrine was so thorough and his practice of the faith so flawless that several influential Church figures had no qualms about entrusting missionary work and pastoral care to him. He was, in short, a star convert. And yet, like that early star convert Qu Taisu who had earned the trust of Matteo Ricci, Zhang maintained his allegiance to the Three Ages movement. Indeed, Zhang even had a hand in setting up a new Three Ages sect, one whose membership of 10,000 souls shows that it enjoyed quite a large reach and influence in Shandong at the time.

The facts of his case refute Franchi’s claim that the sect leaders of 1714 were only superficial Christians. Zhang Paulus was a pillar of the Church in China as much as anyone could be, playing a crucial role in its survival and expansion in Shandong. Franchi himself had even accepted him as a sincere Christian at one time. Given how deeply embedded he was in the Church and the lengths he went through to demonstrate his Christian piety, it is hard to believe that he was merely doing it all for show. But he was also a committed Three-Ages sectarian, one who used his considerable skills at conversion to build up his new sect while also winning souls for Christ. The only explanation for how Zhang Paulus could be both is that, in his mind, these two belief systems did not contradict each other but went hand in hand.

Nor was he alone in this thinking, As Tiedemann states, “there can be no doubt that a significant number of Nieto and Orazi’s converts had connections with divergent indigenous religious groups” (354). The example of Zhang Paulus illustrates that, whatever the Church itself might say, the sectarians were not simply joining Catholicism in order to disguise their true religious beliefs and activities. Rather, the sectarians had a genuine interest in Christianity and its teachings. What is more, even those who became very learned in the faith and experienced with its rituals and doctrines, such as Zhang Paulus, saw Christianity as compatible with the teachings of their own sects. Zhang’s case is significant because it shows that, even when they became fluent in Christian doctrine and reached high levels in the Church hierarchy in China, the new converts could not see much difference between Christianity and what their own Three Ages sects were teaching.

Our first direct clue that this is indeed a Three Ages sect comes from Bishop Della Chiesa, who reports that the leader of the sect was not Zhang himself but a man with the suggestive name of Liu Mingde (劉明德). Sect leaders were very much aware of the power of the names they were known by, and there is no name that could have more apocalyptic meaning for a sectarian than this one. His surname, Liu, is the same as that of the Han Emperors, which ties it back to the ancient prophecy foretelling an imperial savior of the Liu house who will be aided by a man named Li. As we saw from the case of Liu Qi, sect leaders with this surname were very aware of the prophecy and happily applied it to themselves. By this time, they usually interpreted it to mean that Liu would be the earthly surname of Maitreya, the future messiah and ruler of the Third Age. The old Han prophecy had thus become so completely intertwined with the doctrine of the Three Ages that to express faith in it was to express faith in the Three Ages themselves.

Equally significant is Liu’s personal or courtesy name, Mingde. The Ming element is the name of the Ming Dynasty. They are the same word, as both are written with the character 明. This ties Liu into another important apocalyptic prophecy of imperial restoration: the future overthrow of the Qing by a new Ming Emperor. The restoration of the Ming Dynasty had become part of the standard eschatological repertoire among Three Ages sects after the Qing’s founding, as surely expected as the appearance of Maitreya and the dawn of the Third Age. Qing-era sects had already become adept at using both the Han and Ming restoration prophecies to their advantage; we saw how Liu Qi applied the Han one to himself and the Ming one to a few of his disciples. But Liu Mingde might be the first known sect leader to apply the restoration prophecies of the two dynasties to a single person, namely, himself. The term ming also had a longstanding association with apocalyptic saviors like Maitreya and Liu may have been tapping into this older meaning as well.

We cannot know if Liu bore his surname from birth or adopted it for its apocalyptic meaning, but my guess is that Mingde was a courtesy name. Making de (德—virtue) the second element of the compound, as it is in Liu Mingde’s case, is very common in male courtesy names. The courtesy names of both Liu Bei (Xuande 玄德) and Cao Cao (Mengde 孟德) contain it, for instance. If Mingde is Liu’s courtesy name, it is highly likely that, as a commoner, he would have chosen it himself. In this case, he would have adopted it for its meaning and thus we can be confident that he was well-aware of his own name’s apocalyptic significance and the meanings it would carry among his fellow sectarians. By using such a name, then, he was making his own adherence to the beliefs of the Three Ages movement quite transparent.

Liu Mingde himself seems to have lived something of an adventurous life, if the scant records of him are anything to go by. According to our good bishop, he was captured by imperial authorities and imprisoned in Beijing, only to escape from under the nose of the Qing government. But the sect subsequently ran into bad luck when Liu himself died in 1714. Soon afterward, both Church and imperial authorities became aware of them. Like Three Ages sects more generally, this group saw women as spiritually equal to men, allowing them to participate fully in the organization’s rituals and become leaders in their own right. This proved to be the sect’s undoing; one of the women whom they let into their confidence reported them to the missionaries. Subsequently, Zhang Paulus was expelled as an apostate. Despite the Church’s protestations of innocence, the Qing Dynasty launched a new persecution of Christians that was only halted after Miguel Fernández Oliver interceded with the governor of Shandong, with whom he was on friendly terms. Franchi later obtained permission from the imperial court for the Catholics to begin their missionary work in Shandong again.

As Tiedemann notes regarding this incident, “it seems clear that a significant number of individuals and groups with sectarian connections had managed to enter the Catholic religion” (354). Indeed, the number of people Franchi claimed to belong to Zhang’s sect, 10,000, is the exact same number of people that Nieto had converted to Christianity during his five years of missionary work. While it is tempting to think that these were the same 10,000 people, this is probably going too far. But Nieto’s harvest did consist almost entirely of sectarians. A man named Wang Tianbao, whom Nieto had brought into the Catholic Church, would be arrested for sectarianism in 1724 and a Jesuit named Giovanni Laureati claimed in 1719 that as many as 8,000 of the 10,000 Chinese Nieto baptized were sectarians and that Orazi had brought an equal amount into the Church. It is clear from this that nearly all the new converts to Catholicism in Shandong came from the Three Ages sects and maintained their sectarian ties. Following the events of 1714, the Church could no longer pretend that this was not the case. Bishop Della Chiesa himself was forced to admit it, even if he tried to shield the Catholic missionaries from blame by saying, as Tiedemann puts it, “not very convincingly – that the priests probably did not know that they were sectarians” (354). Still, the bishop confessed that ever since Manuel de San Juan Bautista de la Bañeza had begun doing so before leaving Shandong in 1700, it had become common practice to convert sectarians and bring them into the flock, with Nieto, Orazi, Fernández Oliver, Franchi, and every other missionary in the province all engaging in it.

It had been a painful lesson for the Church to learn. But instead of soul-searching or recognizing how little they understood of the Chinese religious landscape, the missionaries responded with the obtuseness that had so hindered the Church’s missionary efforts in China thus far. The old rivalry between the various evangelizing orders flared up again and all the Catholic figures mentioned thus far became embroiled in a war of words over which of them was really at fault for the sectarian fiasco. They were given a period of peace and quiet to do this, for the most interesting event related to the sectarians in the next few years was that in 1717 a sect leader named He Hei’er traveled to Europe in an attempt to gain an audience with the Pope and initiate the Holy Father into his organization. But then 1718 came, bringing with it another round of sectarian-related troubles that once more put the missionaries’ infighting on the backburner.

The Qing Emperor, still troubled by sectarianism in Shandong, had sent an individual to investigate the province and round up sect members. Discovering that the number of sectarians in the province was substantial, imperial officials decided to pursue the sect leaders instead. In January of 1718, the arrests began. One of those arrested was “a certain Zhu, a self-styled emperor who, it was claimed, was in possession of an extensive membership list, ‘with thousands and thousands of names’” (357). Given that his family name was Zhu, the same as that of the Ming royal house, we can tell that by claiming to be emperor, this individual was using the prophecy of Ming restoration and applying it to himself. Thus, his was surely a Three Ages sect. What is more, its reach was vast, seemingly including several converted Christians. Indeed, in March, the imperial authorities expanded their arrests to the Christians and apprehended over fifty converts who had taken on leading roles in the sects while also professing the Catholic faith. Meanwhile, Zhang Paulus was still at large; the Catholic missionaries suspected his involvement with the newly discovered sects and hoped that he would soon be caught in the imperial net.

In February, after the initial period or arrests but before they were extended to the Christians, a curious incident occurred. As Tiedemann tells it:

On 28 February 1718, at two o’ clock in the afternoon, three men came to the Catholic Church in the Grand Canal city of Linqing 臨清, western Shandong. … Two of them apparently were baptized Christians. The third claimed to be a sincere Christian, but was not baptized. Strutting arrogantly, they said in a pompous voice that they had been sent by the ‘great lord’ (dazhu 大主) insisting that Yi laoye 伊老爺 (Bishop Della Chiesa) come out to ‘receive the mandate’ (jie zhi 接旨). … According to them, the great lord was a certain Yang Dele 楊德樂, a bai ding 白丁 (plain person), who claimed to be a great lord, and even the second person of the Holy Trinity, and that he could judge the living and the dead. Thereupon they untied the yellow packet with Yang Dele’s note. Inside two red wrappers (bao 包) were some Chinese papers. One of these was about a person called Liu Mingde 劉明德. The other sheets, one red, one yellow, contained rather unintelligible scribbles. The two or three snatches of Chinese hinted at insurrection[.] (Tiedemann 341)

As the namechecking of Liu Mingde suggests, this was his own sect, having survived the suppression efforts of 1714 and now remerging in the heady days of 1718. Their new leader, Yang Dele, followed his predecessor’s practice of using a name loaded with significant meaning in Three Ages belief. Yang, of course, is the term which the sectarians applied to each of the Three Ages. Our sect leader’s surname is technically a different word, as it does not bear the same character (陽). However, his surname is written with the character 楊, meaning “willow.” Yin Ji’nan had used that character to refer to the Three Ages—whether to shield his teachings from the suspicious eyes of the authorities or out of genuine confusion between two separate characters, we cannot know—and ever since then the sectarians, who always had a particular liking for homophones, used it as a popular alternate designation for the ages themselves.

Furthermore, Yang’s personal or courtesy name, Dele, meaning something like “Joyful Virtue,” is too similar to Liu Mingde’s own, which means “Bright Virtue,” to be mere chance. This suggests that Yang Dele was just as adept as Liu at utilizing the sectarian significance of his name. Indeed, Yang seems to have put much care into crafting a persona for himself that embodied the main doctrines of the Three Ages teaching. Yang emphasized the fact that he was a “plain person,” someone who holds no official rank and is affiliated with no religious order, coming instead from the laity and the common people. This was the exact social class that Three Ages sects portrayed as the elect and from whence they expected the future messiah, a role Yang might have fancied for himself. And as surprising as Yang’s claim to be the second Person of the Trinity may sound at first, looking like an unexpected precursor to the Taiping leader Hong Xiuquan’s later assertion that he was the brother of Jesus, it follows the common practice among sect leaders to claim to be incarnations of one of the buddhas who rule the Three Ages. In this case, Yang Dele did exactly what I proposed the Three Ages sects did with Joachim’s original system, freely transposing a Buddhist symbol and a Christian one that that he feels is basically equivalent.

That Yang felt comfortable enough to do so provides our strongest piece of evidence thus far that the Three Ages sects saw no difference between their own beliefs and that of the Catholic Church. Not only did Yang see the belief system of Christianity and that of his own sect as being the same, but he also confidently expected that others would recognize their equivalence as well. His own disciples certainly did. The three mentioned above considered themselves Christians but still remained a part of Yang’s Three Ages sect and did his bidding. This was only possible if they saw no daylight between Catholic doctrine and Yang’s own teachings. Yang Dele and his three disciples show that the Chinese sectarians viewed the Catholic Church as another manifestation of their own faith, one in the large patchwork of sects that they had recognized since Gongchang as constituting a single religion.

They were so confident in this viewpoint that they even approached the Catholic Church about joining their millennialist rebellion against the Qing Dynasty. Yang Dele, spurned no doubt by the series of arrests of sect leaders, apparently attempted to do what Lin Qing would more fully achieve a century later in the Bagua rising, which was to bring all the Three Ages sects of the region under one banner so that they could resist the Qing together. That he included the Catholic Church among his co-religionists, probably on the advice of his Christian disciples, shows that, for the sectarians, the equivalency between Catholicism and Chinese Three Ages thought was so obvious that that they expected everyone, including the Catholics themselves, to recognize and acknowledge it.

In this last surmise, they were tragically mistaken. The Catholics, horrified both by the strange beliefs and apparent apostacy of Yang’s disciples and by the suggestion of armed rebellion, meted out physical punishment upon the converts and turned them over to the authorities. The three were included in the March series of arrests that targeted so many converted Christians and Yang Dele was apprehended a little while later. All the imprisoned Christians and sectarians were put on trial but, despite the Qing Dynasty’s otherwise routine severity, managed to escape with surprisingly light sentences.

Most of the Christians managed to bribe their way out of severe punishment. When they returned home, they were spurned by the Catholic Church and instead turned their efforts to expanding the Three Ages sects, with much success. Yang Dele and his three Christian associates were banished to Fujian but managed to escape by bribing the officials charged with transporting them to that far-off province. In 1719, the Emperor issued a general amnesty for the sectarians caught up in the previous year’s arrests, putting a decisive end to the matter. It did not apply to Yang and his Christian companions. Two of them were later apprehended, but Yang Dele and his other compatriot—a man named Niu San—eluded the authorities. That same year, another Chinese convert, Thomas Wang Ermu, was put on trial for murdering his wife after she tried to leave the Church. During the trial, despite a loyalty to Catholicism so strong he was willing to kill for it, Wang Ermu was accused of being a member of Zhang Paulus’s sect. His story provides a strange postscript to the events of 1718 and proves, once again, that the sectarians saw no contradiction between being devout Christians and loyal members of Three Ages sects.

After this final trial, things seemed to cool down in Shandong for a few more years. But they heated up again in 1724. The governor of the province arrested three more Catholic converts. These three were revealed to also be sectarians, having been initiated by a man named Yang Delu 楊得錄, who despite the slightly different personal name with a homophonous character for de, is surely the vanished Yang Dele. The arrest of another Christian convert who had joined the sect in 1728 revealed that it was then being led by Niu San, Yang Dele’s also-vanished confederate. Thus, ten years after the arrests of 1718 and fourteen years after the death of its founder, the sect had not only survived but was thriving in Shandong—the governor mentioned that it had expanded into new parts of the province.

Crucially, it had lost none of its appeal to Christians; they were still joining in large numbers, apparently without seeing any contradiction between this faith and Christianity. And the sectarians were still directing their efforts at Christians, despite the fact that in 1724, Christianity itself was outlawed by the Qing Emperor and prescribed on the same level as that old boogeyman, the White Lotus Teaching. For all the claims that they were merely using Christianity as a cover to hide their true religion, the sectarians did not stop associating with it even after it became just as illegal as their own sects. If anything, this move by the Qing court probably convinced the sectarians even further that Christians were their brothers and sisters in faith.

In the aftermath of the 1718 incident, Miguel Fernández Oliver undertook an investigation of this sect that kept causing so much trouble for the Church and wrote down his findings. His account is not perfect—he uncritically accepts the Qing Dynasty’s contention that the Shandong sects grew out of the non-existent White Lotus Teaching and includes several false claims that had long been part of the imperial playbook for discrediting heterodox groups—but he does fill in many of the gaps surrounding our knowledge of the sect led first by Liu Mingde and then by Yang Dele. For instance, he provides us with a name for the group, Xinglijiao (性理教—Teaching of the Natural Order or, in Fernández Oliver’s rendering Doctrine of Reason and Naturalness), though they often changed their name to avoid detection, as Three Ages sects often did. For this organization was indeed a part of that movement. The record of them penned by Fernández Oliver contains all the telltale signs that we have come to expect from such groups, confirming beyond any reasonable doubt that the Xinglijiao were in fact adherents of the Three Ages teaching.

Fernández Oliver reports that Liu Mingde, the founder of the Xinglijiao, had originally been a soldier from Shandong. He shared this distinctive background with two of the great sectarian founders, Patriarch Luo and Puming, and was no doubt inspired by this to follow in their footsteps—one is tempted to wonder if Liu Mingde was also an orphan. That this bit of backstory was given such importance among the sect, so much so that a Catholic missionary was able to stumble upon it, suggests that Liu Mingde himself made it a key part of his persona as sect leader. This strengthens our earlier supposition that Liu Mingde, in his public presentation, deliberately invoked important aspects of Three Ages beliefs. In this case, he emphasized his similarity to two of the reputed founders of the movement in order to legitimize his own position as founder of a new Three Ages sect.

Furthermore, the Xinglijiao was divided into eight sub-groups called the bagua and based on the Eight Trigrams. This, of course, had become the ideal form of social organization promoted—but less often put into practice—by the Three Ages sects. It was a distinguishing characteristic largely unique to them and gave its name to their Bagua rebellion in the next century. Members advanced in the sect by acquiring special titles—a sectarian practice first mentioned in the first known Chinese Three Ages text, the Huangji jieguo baojuan. Apparently, they had to pay a fee to the sect leaders for these titles, which was another common sectarian practice. Fernández Oliver makes the claim that sect members “do not take much notice of their women” (qtd. in Tiedemann 361), which would suggest an uncharacteristically low opinion of women in this sect when compared to others of the Three Ages tradition. But he contradicts himself by noting that it was often women who purchased and held high-ranking titles in the sect such as “queen, vice-queen, wife of a gelao [閣老¸ secretary of state]” (qtd. in Tiedemann 361), which is more in-line with our understanding of how the sects in the wider tradition treated and regarded women. All this information suggests that this group was a very standard example of a Three Ages sect.

And like the other Three Ages sects, the Xinglijiao employed esoteric rituals that centered upon the recitation of an eight-character secret mantra. This mantra was zhenkong jiaxiang wusheng fumu (真空家鄉無生父母), which Fernández Oliver mistranslates as “the true sublunar space is my home and town. I have no other father or mother that created me” (qtd. in Tiedemann 361) but which is better rendered “Unborn Parents in the Native Place of True Emptiness.” “Unborn Parents,” or more literally “Unborn Father and Mother,” is a term that was attested by Patriarch Luo but by this time had been taken up by the Three Ages sectarians. It could be used to describe two actual Persons in the Godhead, one masculine and one feminine, as in the Longhua jing. But just as often, it meant the One God without distinction, a single being that is both father and mother of everything. In this sense, it was often applied to the supreme deity of Three Ages sects, whether that entity was imagined as the Primordial Buddha, the Unborn Mother, or (most frequently) a combination of both. Thus, we can confidently assert that the Xinglijiao worshipped the Venerable Unborn Mother as their chief deity. And wherever veneration of the Unborn Mother was found, belief in the Three Ages inevitably accompanied it. Thus, this group’s devotion to the Mother is one of our strongest pieces of evidence that they also upheld the concept of the Three Ages.

But an even stronger piece of evidence comes from another name by which their sect was known, as recorded by Carlo Orazi himself: the Sanyuanjiao (三元教). This name, which means Three Primes Teaching, uses the terminology of the old Taoist concept of the three yuan but evidently refers instead to the universe-spanning Three Ages of Chinese sectarianism. Interestingly, the governor of Shandong in his report on the 1724 incident also claims that the sectarians involved also belonged to a group of a similar name, the Sanyuanhui kongzijiao (三元會空子教—Three Primes Assembly of Emptiness Teaching), which confirms that this is the same group behind the events of 1714 and 1718, that it was still made up largely of converted Christians, and that it did indeed espouse a belief in the Three Ages of cosmic time.

The weight of this evidence is enough for Tiedemann to conclude that this was indeed a Three Ages sect that, like the rest, held to “the notion that time was divided into three immensely long eras or kalpas. The end of the present second kalpa would be accompanied by great cosmic catastrophes which would destroy the world, ushering in the final kalpa … the turning of the kalpa would radically transform the terrestrial realm. ‘In this new world, justice, plenty, and a long life would prevail, and loyal sect members would attain high sect status’” (362-63). If Tiedemann is this confident, even citing a quote from Overmyer—one of our oft-cited experts on Chinese Three Ages belief—there is no reason for us not to be. We can thus say with certainty that the Xinglijiao were very much a Three Ages sect and held to the standard set of beliefs regarding the immediate arrival of a utopian Third Age of history. What is more, they clearly expected the Catholic Church to share their sense of anticipation for the age to come.

But why did they expect this? What would make Three Ages sectarians so interested in joining the Catholic Church and enlisting it as an ally against the Qing Dynasty, even as the Church jealously guarded its claims to exclusive truth and bent over backwards to stay in the good graces—such as they were—of Qing officials? Was it a peculiar quirk of this one sect, the Xinglijiao, or of the sectarians in Shandong specifically? Evidence from other regions in China suggests that this was not the case; sectarians across the country viewed the Catholic Church as another branch of their own religion. For instance, the rival “Catholic Church” set up by the sectarians in 1703 managed to not only spread to Henan but had amassed, as Fernández Oliver lamented, “many thousands and even millions” (qtd. in Tiederman 369) of followers there, with their sectarian brand of Catholicism far outpacing the actual Catholic Church in that province. Clearly, the interest in Catholicism among sectarians was not something unique or particular to Shandong.

What accounted for the special interest that the sectarians took in Catholicism? There clearly must have been something about the Catholic faith that appealed to them. They were certainly not convinced that Catholicism was the one true faith and that their former beliefs were mistaken, for they maintained those beliefs and membership in the sects that spread them even after joining the Church. And the source of the appeal had to be something specific to the sectarians alone. The Catholic missionaries had already attempted to convert every social group and class in Chinese society using the same methods, arguments, and forms of preaching that they used on the sectarians, only to be met with a near-universal lack of interest. But the sectarians came to them of their own volition, in large numbers, when no one else did; it was only upon noticing this that the Church itself turned its particular attention to them. Something led them, as believers in the Three Ages system and its doctrines, to conclude that the Catholic Church would be an appropriate place in which to practice their beliefs. Not only that, but it also convinced them that the Catholic Church espoused the same beliefs as they did. What was that something? I suspect anyone following the course of this series will already be able to hazard a guess. But I shall discuss it in depth next time, in what shall be the final entry in this series.

Works Cited

Liu, Yu. “The True Pioneer of the Jesuit China Mission: Michele Ruggieri.” History of Religions, vol. 50, no. 4 (May 2011): pp. 362-388.

Tiedemann, R. G. “Christianity and Chinese ‘Heterodox Sects’: Mass Conversion and Syncretism in Shandong Province in the Early Eighteenth Century.” Monumenta Serica, vol. 44 (1996): pp. 339-382.