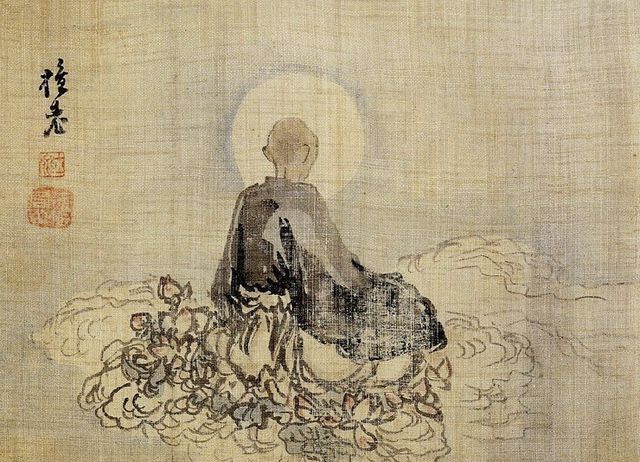

Kim Hong-do

(1745-1806)

Why is it that a person of the intimate way cannot cut off the the vermillion thread, that thread of tears?

from Songyuan’s Three Turning Words collected in the Harada Yasutani Miscellaneous Koans

A few of us in my broader Zen family have been discussing this little koan from our traditional curriculum. The kick off for that conversation was an observation about that vermillion thread. Sometimes the red-purple thread. Sometimes the red thread. Within our received tradition the thread is interpreted as the line of birth and death and in our community has something of a sexual implication in it, at least a sense of birth and blood. And it would probably behove the student of the way to recall where there’s birth, there’s death.

One of our band suggests as the characters read 明眼人、因甚脚跟下、紅絲線不斷 that the thread of tears is added. And with that perhaps superfluous. It does appear to be unique to our line.

At bottom, what we’re called into with the whole project is our awakening. A most lovely and terrible thing about this project is in the first and a most wondrous step is to move from our sense of isolation, false to the degree we cling to it as some core sense of a separate being. Then we discover the unraveling of all our ideas about things. Or, to use another image, burned away. Or, in another into a direct and intimate tumble beyond anything that can be grasped. As one teacher said, the bad news is we’re all falling. The good news, however, is that there is no bottom. The grasp loosened, the unraveling of ideas, a great burning away, a tumble.

And while we’re not talking of a thing in any of the sense of our grasping, there is nonetheless a step beyond that loosening, unraveling, burning, tumble.

We find it expressed in that line from the Heart Sutra, “form is emptiness, emptiness is form.”

The larger part of our formation as people on the intimate way takes place after we notice the exact identity of our contingent being and the boundless.

Those of us who undertake this way occasionally find ourselves called into what in the West is sometimes designated the cure of souls. We become spiritual directors. There are several paths to this task. The more common is that this takes place among monastics or in the Japanese inheritance, priests.

But the acknowledgement of a teacher is separate from monastic or priestly vocation.

Transmission is its own thing.

The language of transmission is rather grand. And it deserves it. And there is a sense in which it is always oversold. It is in fact a hope. A dream. A recognition more of possibility than certainty. That empty is, after all, nothing other than this body of causes and conditions. And therefore, always, always, we are subject to being wrong.

But there is a great hope that is being expressed, a confidence, a trust.

Me, I received that sign of trust from John Tarrant. He received it from Robert Aitken. He recieved it from Koun Yamada. And he from Hakuun Yasutani, who received it from Daiun Harada, and so on into the great mists of time and myth.

We claim all the way back to Gautama Sidhartha. The vermillion thread. The line of tears. The line of laughter. The line of sorrow. The line of love.

A line of transmission.

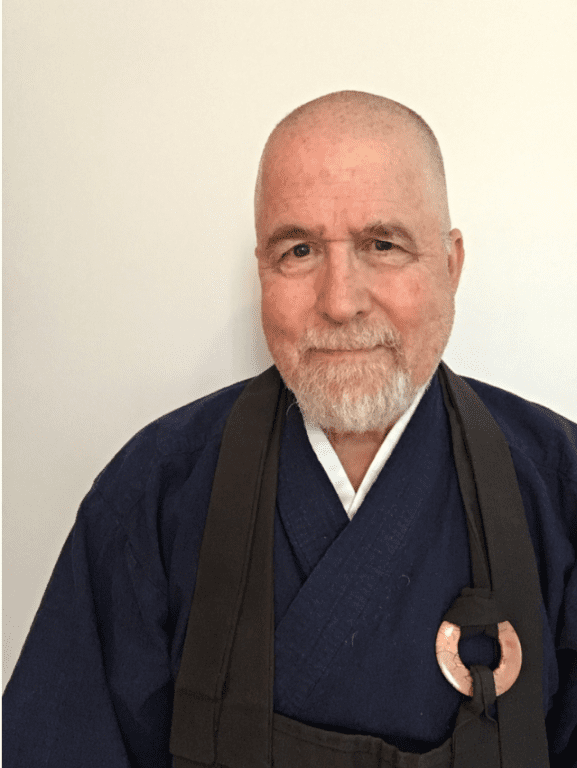

On the 16th of June, 2024, before a small gathering in an private ceremony of acknowledgement, I gave Inka Shomei, the last of the possible authorizations I can offer on this way, to my brother and friend and companion on this terrible and wonderful way, Edward Sanshin Oberholtzer.

In our lineage the title that goes with this is roshi. The term is more an honorific, it really just means venerable elder. As in old fart.

We tend not to use titles in our community beyond for advertising purposes. It allows seekers a sense of how we stand in relation to other Zen communities. And. These things are all overdone. Which I am certainly aware. While there are moments of recognition, like this ceremony, the proof of our pudding takes place in the arc between our individual birth and our individual death. Small knots in that vermillion thread. Only time will tell…

But. Hope. Dream. Possibility. Trust.

Each of those are threads woven together as this life.

May Ed be a solace for the broken hearted, and a true guide for those called into the intimate way.

What follows is Ed’s most recent dharma talk. Gives you a flavor of the teacher.

Seeking a guide on the intimate way is a very personal thing. There are different right teachers for different people.

But if you’re looking, check him out…

GOOD FOR NOTHING

Edward Sanshin Oberholtzer

My son writes music with time signatures so complex that the conductor preparing a piece for performance utilized a click track in order to follow the progression of the music, a kind of acoustic grid laid down to navigate the pages of the score, just as the tree branch tip, tip, tipping against a window in the Wellington Museum guides the reader in early twentieth century Ireland in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake and leads them through the prosaic maze of Joyce’s vision, one tip at a time. We have inherited a view of time that sees it as the part of the canvas on which our lives are painted, as separate and fixed.

But this rigid grid, this beat of a conductor’s baton, this ticking of a watch or a tree branch, is not how we experience time And, however precise it might be, it doesn’t point to this very moment in which we find ourselves.

My mother once gave me a bag with a number of watches that had belonged to my father. The watch I wear today is one of them, an old aviators watch that predates my own birth and that, despite its allegedly being a chronometer, keeps time now only approximately. I treasure its inability to acknowledge the passing of time with anything approaching precision. Perhaps it points to a more humane sense of time, a lived moment.

Our Japanese Zen ancestors had ways of tracking time that have a lovely sense of the imprecise. Days divided into twelve hours that stretch and contract with the seasons. Drum beats and gongs that mark the hours into thirds and no more.

Dai-En Bennage, the Soto priest who, oddly enough, lives down the street from me here in Lewisburg and who spent decades studying and practicing the Dharma in Japan, liked to recount that during periods of zazen she used to sing to herself 99 bottles of beer on the the wall to get through a sitting period, 99 bottles of beer on the wall, 99 bottles of beer, Won’t someone ring that God damned bell, there’s 99 bottles of beer on the wall. You had to have met her to know how wonderfully incongruous that “Won’r someone ring that God damned bell” was. The New York times, in 1929 related an explanation from Albert Einstein explaining the relativity of time. I’m sure, I know it misses the points Albert raised in his Special Theory of Relativity, though it sits well with Dai-En’s sense of a sitting period stretching on into a kalpa. The quotation runs – Numerous anecdotes are being circulated concerning Einstein. He once told a girl secretary when she was bothered by inquisitive interviewers, who wanted to know what relativity really meant, to answer:

“When you sit with a nice girl for two hours you think it’s only a minute, but when you sit on a hot stove for a minute you think it’s two hours. That’s relativity.”

Speaking of relativity, Nagarjuna assures us that time, like all things, is empty, defined by its relationship with all around it – Einstein’s explanation involving the stove and a pretty girl. Dai-En’s quiet recitation of that old drinking song matched against the 40 minute standard Soto sitting period.

Now, I use to collect records of old blues guitarists, Son House, Robert Johnson, Blind Willie Mctell. When I think of “Being present”, of that old response to an elementary school teacher’s morning role call, my mind instantly falls back to Mississippi John Hurt and his rendition of “Here am I, Oh Lord, send me” Not the response of the Prophet Isaiah, nor of all those others who heard the call of their god. No, that jaunty rag time blues guitar of John Hurt waking me up, grounding me. Just like that child in a spring time elementary school classroom so many years ago saying “Present!” Just like Ananda answering Yes! to the call of Mahakasyapa. Right here, right now. So we hear the exchange between the second ancestor and Ananda in case 22 of the Gateless Gate, Mahakashyapa’s Flagpole

Ananda asked Mahakasyapa, “The World-Honored One transmitted the robe of gold brocade to you. What else did he transmit to you?”

Kasyapa said, “Ananda!”

Ananda answered, “Yes!”

Kasyapa said, “Knock down the flagpole at the gate.”

Ananda answers in that instant, with no separation between call and response. “Ananda” “Yes!” “Isaiah” “here am I!” “present!” Kasyapa acknowledges his understanding with “Knock down that flagpole at the gate”, the lecture finished.

I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for Ananda, the Buddha’s cousin, the man with the perfect memory. Too many memories, too many thoughts. How many times had that brain, has my brain, has your brain stood in the way of just being here? You know the drill, walking down the stairs and suddenly thinking about where your next step should go. But perhaps I expect too much from Ananda. He was famous for attending each of the Buddha’s talks, for retaining them in his memory, for reciting them later, after the death of the Buddha. “Thus have I heard”, each sutta beginning with this acknowledgement that Ananda was there, present, listening. Quietly, present in stillness, awaiting each word. Here am I, oh Lord, send me!

But it’s easy to say just be here now.Just be present. Aren’t we all just here now? But just when is that? There’s a kind of saddleback between the future and the past. This moment, flowing out of the past, flowing on towards the future, but neither one nor the other. Timeless. Just this moment. In an interesting take, the poet Billy Collins put his finger on something like it in the poem “The Present”, where he writes:

The trouble with the present is

that it’s always in a state of vanishing.

Take the second it takes to end

this sentence with a period––already gone.

What about the moment that exists

between banging your thumb

with a hammer and realizing

you are in a whole lot of pain?

What about the one that occurs

after you hear the punch line

but before you get the joke?

Is that where the wise men want us to live

in that intervening tick, the tiny slot

that occurs after you have spent hours

searching downtown for that new club

and just before you give up and head back home?

That moment, the eternal now between past and future. Wittgenstein observed that “[i]f by eternity is understood not endless temporal duration but timelessness, then he lives eternally who lives in the present.” And Brad Warner reminds us that you are always in the moment. You can’t be more in the moment no matter what you do, because you can’t ever escape from being exactly here and now, except, of course, that it is so easy to think that you’re somewhere else. As he writes:

“All you can do is fail to notice that you are already in the moment. That can be a problem. You can make a lot of mistakes by thinking you are somewhere other than right here, right now. You can make a lot of mistakes by thinking that this moment is preparation for some other moment in the future. What pulls you out of this moment is the idea that this moment ought to be good for something outside of this moment.”

And here’s the thing about this moment, it’s nothing special. No heroics

Nothing big. Nothing grand. Chopping wood with that old man, Layman Pang, carrying water with his family of worthies. The mundane, the everyday, the boring. Milton tells us that “They also serve who only stand and wait.” And what more mundane function is there than being the keeper of the gate? When Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote the poem entitled In Honour Of St. Alphonsus Rodriguez, Laybrother of the Society of Jesus, he wrote of everything that this moment is not and everything that it is.

Laybrother of the Society of Jesus

Honour is flashed off exploit, so we say;

And those strokes once that gashed flesh or galled shield

Should tongue that time now, trumpet now that field,

And, on the fighter, forge his glorious day.

On Christ they do and on the martyr may;

But be the war within, the brand we wield

Unseen, the heroic breast not outward-steeled,

Earth hears no hurtle then from fiercest fray.

Yet God (that hews mountain and continent,

Earth, all, out; who, with trickling increment,

Veins violets and tall trees makes more and more)

Could crowd career with conquest while there went

Those years and years by of world without event

That in Majorca Alfonso watched the door.

Just here, just now. Watching the door, through days and years. Doorman as saint. Sitting on a cushion through what certainly feels like kalpas. Counting the 99 bottles of beer on the wall. They also serve who only sit and breathe. And in that sitting, in quiet awareness, we may ask ourselves, with Homeless Kodo, “Just what is all this good for?”

In order for zazen to be good for anything, it has to be good for nothing. Kodo Sawaki reminds us: “What is zazen good for? Good for nothing. As long as this good for nothing practice does not penetrate our bones and we really practice what is good for nothing, it won’t be good for anything,” Practice, work, sitting.

Yet sitting, being here, breathe in that summer breeze, Notice the rise and fall of your chest. Hear the songs of the birds, too absorbed in their day to day existence to notice anything beyond the simple joy of being alive, of being here. Sit upright on that zafu. Sit here with Otis Redding,

Sittin’ in the morning sun

I’ll be sittin’ when the evening comes

Watching the ships roll in

Then I watch them roll away again, yeah

I’m sittin’ on the dock of the bay

Watchin’ the tide roll away, ooh

I’m just sittin’ on the dock of the bay

Wastin’ time

And no, no, he’s not wasting time, he’s just here, being good for nothing.